by William Park

Actual horror lies in the imprisoned psyche. Japanese cinema, as far back as the 60s, has captured the essence of this territory. I’ll refer back to the 60s in this short introduction to Japanese horror, while describing some of the key films from the 90s and beyond.

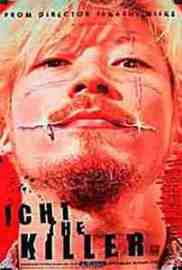

Ichi The Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001) is best described as a Yakuza (crime) thriller, with horrific elements – and Miike’s earlier work, Audition (1999), is more specifically in the genre.

Unease is created in Ichi, through disorientating camera angles, pumping frenetic music, sudden violence – but grotesque torture doesn’t disturb the depths of the psyche, merely shocks and provokes. Where this film does disturb, is through the killer Ichi’s childish, baffled visage, his bouts of crying, so at odds with the merciless violence he unleashes. In the meleé of grotesque mutilation, screams, and ludicrous blood-letting, there is a core of horror – in the relentlessness of pursuit leading to death. This claustrophobic narrowing confines the viewer to a specific world of freakish violence.

Far from being mere fantasy, horror draws on underlying fears we experience, about threat, uncertainty, death, and even love.

Audition takes 45 minutes to bring us to the image of Asami’s bent figure, her long black locks (a hairstyle as sinister as Sadako’s in Nakata’s Ring) draped to the floor, while she concentrates on mentally forcing Aoyama to phone her. It’s seductive, sweetly disturbing, together with her words ‘Please love me. Only me…’ and her subsequent disappearance – as much a part of the instruments of manipulative torture as any of the final explicit scenes.

Aoyama’s ordeal by Asami’s needle and wire is lengthy, but the one shot shown in silence, through a double-glazed window, is, being muted, the most effective scene. The depth of character in the film – ‘ballet purified the dark side of me’ comments Asami – contributes to our horror at the dark side’s emergence.

The classic Onibaba (written and directed by Kaneto Shindo, 1963) takes us further. It begins with frenetic drum-beats, Stravinsky-strident brass (the score is by Mitsu Hayashi) and sinuous, waving reeds…such imagery working with anticipation and the half-hidden – then, the Valkyrie-like intensity of the female characters, their vengefulness, readiness, and intent to kill, chills.

Their rock-killing of a dog (for food to eat) is both realistic and upsetting. The fear within both women starts to work on the viewer’s psyche, via the terrified expression of the daughter-in-law, hearing the description of hell realms, or the widow, scared by the masked samurai.

Atmosphere is conveyed through haunted expressions, the cawing of crows, and stark black and white photography at waist-high, confining, Ozu-style level.

The use of wide-angle lens creates claustrophobic intensity in Freezer (written and directed by Takashi Ishii, 2000). Ishii started as a Manga comic book artist, and this film reunites him with previous collaborators, cinematographer Yasushi Sasakibara, and musician Goro Yasukawa. The clarity of shots, close-ups, and blending between scenes (including snow falling in lamplight) gives poetic beauty to a film about a young woman storing bodies in freezers!

But the confinement to scenes, largely in Chihiro’s flat – a setting comparable to Repulsion (Polanski, 1965) – Polanski, incidentally, having influenced Hideo Nakata’s Dark Water – and the psychological distress inflicted on the previously buoyant Chihiro, her elfin-like vulnerability, lays the groundwork for the horrific change in her – ‘They’re so beautiful when you freeze them’. It’s not so much the brutality she inflicts in her defence against the previous gang-rape members’ return, which disturbs, but the degree to which her mental suffering corrupts her.

Based on a novel by Kôji Suzuki, Ring (Hideo Nakata, 1998) plays on deep-seated fears about death, destiny, and mental imbalance, and places it in the modern idiom. Skilfully, the medium of artefacts (video, telephone, photograph) are mostly used to depict aspects of threat and horror, while the ‘ordinary’ life of suburbia – school, work – continues.

A similar contrast is set up in Haneke’s recent Hidden (2005). The video curse ‘You will die in one week’ is more frightening for accumulating in piecemeal fashion, through anticipation, rumour, superstition.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, Cronenberg’s films played on deep-seated anxieties about infiltration, physical vulnerability, mental disturbance (including Spider in 2002). Here, in Ring, vengeance and threat is a psychological virus. It works, too, on our fears about retribution from the dead, and Sadako’s mental link to the elemental power and mystery of the ocean stirs up further unease connected to the unknown. Kenji Kawai’s unsettling music (inspired by Dario Argento’s Suspiria soundtrack) is used sparingly between moments of quiet and reflective build-up.

Ring 2 (1998) succeeds a little less, because strangeness in this sequel arrives more quickly, the disturbing experiences being more widespread and correspondingly more diffuse. Another problem is that the information conveyed by the screenplay is necessarily retrospective. The ‘exorcism’ in the final stages, is also over-elaborate. But the essential vivid mythic drama – of loss and vengeance captured on videotape through psychic transmission – retains its power to unsettle and horrify.

A short story by Kôji Suzuki inspired Dark Water (Hideo Nakata, 2002) which begins with creepy ambient music (Kawai again) and semi-identifiable imagery. Otherworldliness is created through the grey zone scenes from the surveillance cameras at the apartment block, and credit must go to the cinematography of Junichirô Hayashi, and the atmosphere created from the flat itself, the drab grey, green, whites and browns, the rain and damp, and a combination of realistic set-backs encroaching on the affectionate relationship developed between Yoshimo, the mother, and her 6 year old daughter Ikuko (‘I don’t need anyone but you’ says Ikuko to Yoshimo).

In Dark Water a ‘Mimiko’ red bag, or a damp, dripping ceiling, can convey threat…the half-seen alone, isn’t, in my view, enough to transmit horror – as The Blair Witch Project (Myrick/Sanchez, 1999) strained to achieve – what’s needed, exemplified in Dark Water, is a counterbalancing reality of hope, normality, and depth of character.

Hideo’s film has a comparable mythic resonance and power to The Devil’s Backbone (Del Toro, 2001).

The ending is exquisitely tender, without escaping completely the real horror which remains.

Mark Kermode in Sight & Sound (August, 2005) is right to highlight the importance of the spirit world in Japanese culture, how this brings an added depth and dimensionality to films like Dark Water and Ring. This would apply to Onibaba also.

I would stress the importance of emotional depth too, conveyed through characterisation, cinematography, and sound – which all play their part in a slick, but poetical, thriller like Freezer. Only when these elements are focused, in harmony, and treated sparingly, real horror emerges, insinuating – not at the level of visceral sensation alone – to the heart, our human emotions, our fears.

(This piece previously appeared on http://www.pennilesspress.co.uk/)

~

William Park received a Major Eric Gregory Award (1990) and Hawthornden Fellowship (1991). His poems have appeared in Poetry Review, The Observer, Critical Quarterly, The Rialto, Stand, Poetry Wales, Ambit, Poetry Durham and numerous magazines/anthologies over the past 25 years. He has an MA in Writing and Reading Poetry (Liverpool Hope, 2003). His first full poetry collection was Surfacing (Spike, Liverpool, 2005).